The role of regulators in the origin of multi-cloud

July 7, 2023.

I was recently a guest on a podcast with Rick Taylor (the CTO of Ori) where we briefly discussed some of the regulatory origins of "multi-cloud". This topic led to several follow-up questions from listeners which I wanted to dig into.

To give you some background, I've been in and around "public cloud strategy" for about 15 years. First as a technology leader at a hyperscaler (Azure) and then as a consultant working with lots of large organisations on cloud strategy and "cloud transformation" (at McKinsey & Company and as an independent advisor). I've also spent a lot of time speaking with regulators about the public cloud, particularly in the UK, the US and Europe.

Laying out my biases upfront, when "multi-cloud" first emerged I was a heavy, cynical sceptic, and while I broadly remain that, I've softened over the years as I've spent time with people outside technology who are stakeholders in this problem.

What is multi-cloud? Where did it come from?

The idea is a pretty simple one: that an organisation can deploy its cloud workloads into multiple providers at the same time, based on some criteria that's important to that business. Why they would want to do that, and how they would go about doing it, are something else entirely.

In my experience, the genesis of "multi-cloud" came from three sources:

- Governments, via regulators, concerned about systemic risks

- Legacy technology companies who were failing at creating their own cloud businesses and so poured billions into creating the "multi-cloud orchestration" market segment

- A quasi-religious anti "vendor lock in" philosophy at large enterprises, built in the previous 10-years hard work in decommissioning proprietary technology

I may follow up with seperate posts on (2) and (3), but for now, we'll focus on regulators and the role they played in the emergence of "multi-cloud".

The regulatory origin of "multi-cloud"

In the early 2010s, large regulated businesses (like banks, pharma and defence) were starting their glacial progress into the public cloud. They did this as all sensible regulated businesses should and started talking to their respective regulator.

The regulators didn't know much about the public cloud (some might uncharitably argue they still don't) so off they went and learned more. The regulators also went to the governments of their respective countries, who play a major role in setting regulatory policy. This took a while. A long while. Years.

Like many superficially simple questions to regulators ("Can we use the public cloud?") they eventually answered with an enigmatic "it depends". When pressed they clarified with "we want to take a risk-based approach, some of you can go ahead into the public cloud, but you need to follow this arbitrary set of rules. Some of you are so important to our economy/defence/public health that we're going to say no, for now".

This happened in many industries and many countries, for example, it's how banks in the UK cloud be built from scratch in the public cloud while others that were seen as more systemically critical to the UK economy and were told to hold off. If Monzo broke because of the public cloud it's bad but manageable, but if Lloyds breaks it could push the UK economy into recession. A risk-based approach.

As regulators learned more from these early experiments with the public cloud (as did their bosses in central government) they started to soften on these more important, systemic regulated entities. They then said things like "We're nervous this critical part of our national defence is on a public cloud controlled by another country" or "We're nervous that such a significant part of our economy is dependent on a single public cloud company" but if these regulated industries could mitigate these risks, they too could start reaping some benefits of the public cloud.

For many people at the time, a lightbulb went off: what if we used multiple public clouds? That would surely mitigate at least some of those risks!

But what are the underlying risks these regulators care about?

Geo-political risk

One of the key drivers of this policy is geopolitical risk. Let me give you a hypothetical example:

This (completely stupid) example paints an important point: the public cloud is perceived as a US strategic asset, and moving entire critical parts of your national infrastructure onto it could (arguably) put you in a very precarious position that you haven't been in before. The US are friendly now, but will they always be?

As technologists, we may scoff at this as spectacularly unlikely, but if it's your job to think about unlikely but impactful scenarios for your country, could you scoff quite so hard?

Concentration risk

A term often used by people who work with risk is "concentration risk" which is a lawyer'y way of saying "Don't put all your eggs in one basket"; in this case, a single basket that may suffer from region wide network connectivity failures.

This risk, concentrating too much of your important infrastructure in one place, is a key driver for lots of different regulatory provisions but particularly so as a driver for multi-cloud. This is something that technology people can usually understand. Rather than making sure your service is in more than one availability zone or more than one region, for reliability and safeties sake imagine it was in more than one cloud provider.

This is true at a sector level, for example, it's important there isn't just one cloud provider any regulated entity can choose from, but it's also true (and usually more relevant) at the level of individually significant entities.

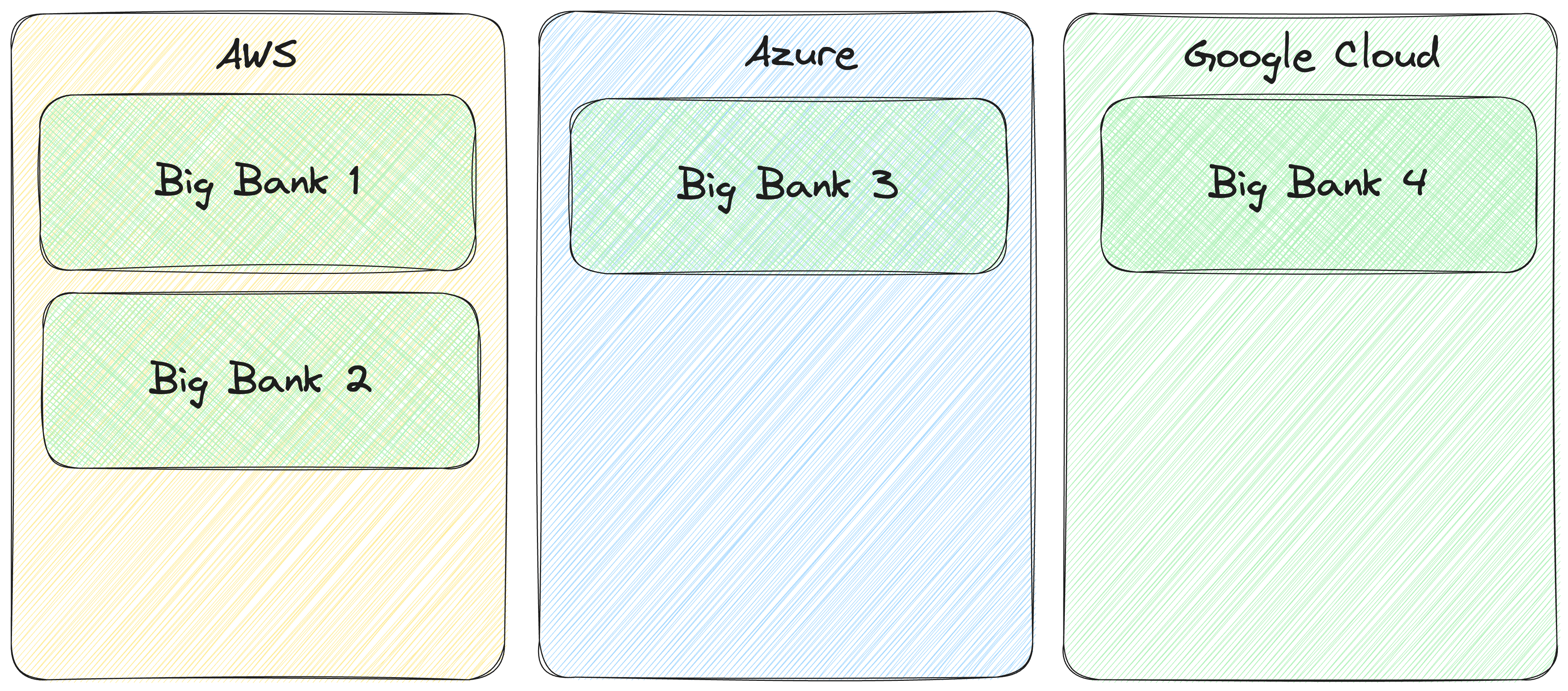

Considering the example in the figure above, you might think that this is acceptable. If an issue occurs with one cloud provider, it doesn't affect all the Big Banks, but as in real life and in this example, each bank is systematically significant by itself. Big Bank 2 failing is a Bad Thing™ for the economy.

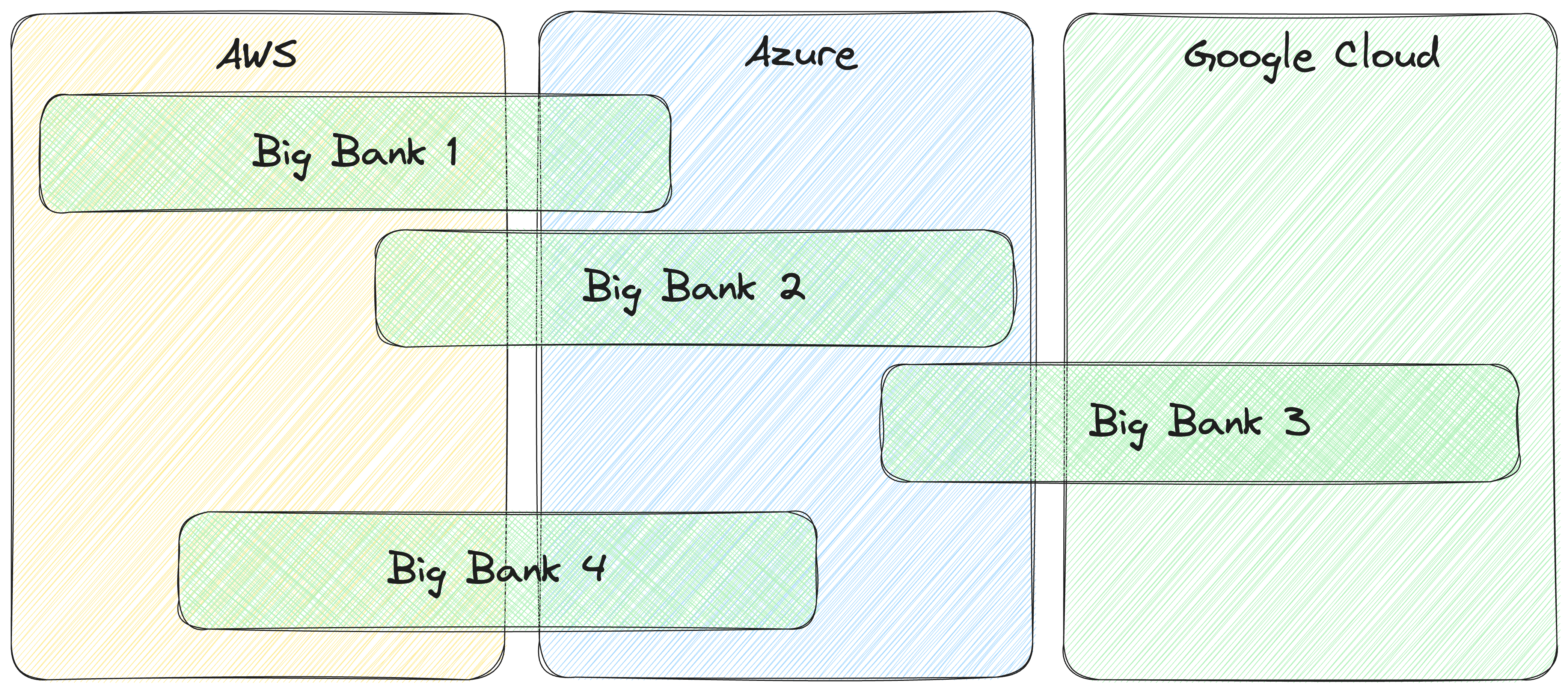

A better setup from a regulatory and risk perspective is where that "concentration risk" is mitigated at the entity level. Where each regulated institution has their cloud usage spread across >1 provider. As in this second figure, in reality a regulated business like this will have a "primary" and "secondary" cloud provider with "most" capacity being run by a primary supplier.

For you, the individual or even your organisation, the benefit of doing that is very small, as it doesn't mitigate any realistic risk for you or you business (for example, running across multiple regions at a single provider mitigates most of the technical reliability risk of being in one provider); but at much larger scale (as in the Japan example above) it might prove to be very beneficial.

Planning for the unlikely

Most people look at these two risks and assess them as highly unlikely, and when balanced with the significant cost and complexity of multi-cloud, think they're bad decisions. I have sympathy for this perspective, but we need to consider that it is the job of these regulators to plan for superficially unlikely scenarios. If all they made were plans for what was likely to happen, they wouldn't be doing their job.

When this regulatory pressure is combined with the massive influence of providers like IBM and Oracle lobbying for multi-cloud as a commercial opportunity, and 20-years of scar tissue in these companies of trying to get away from "proprietary" solutions (which if you squint look a bit like the public cloud) you end up with companies embracing multi-cloud.

Related posts

- 'Founding' in an open technical role is a signal you don't want that job

In practice, technical roles advertised with the word "Founding" in the title are usually a compensation downgrade presented as a title upgrade.

Published on April 29, 2024 in Tech

- CTO Primer: Technical Due Diligence1.1

What happens during an investor technical due diligence? What are they looking for? How does it work?

Published on August 17, 2023 in Tech

- Running Scrivener on Linux

I'd been attempting to configure Wine for months in order to make the writing app Scrivener work on Linux, but then I discovered Bottles and got it running in less than 15 minutes

Published on December 31, 2021 in Tech